Did Egypt’s State Budget Really Not Fund the New Administrative Capital?

The Egyptian government, led by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, has repeatedly claimed that the New Administrative Capital (NAC) was financed without burdening the state budget, relying instead on land sales and private investments.

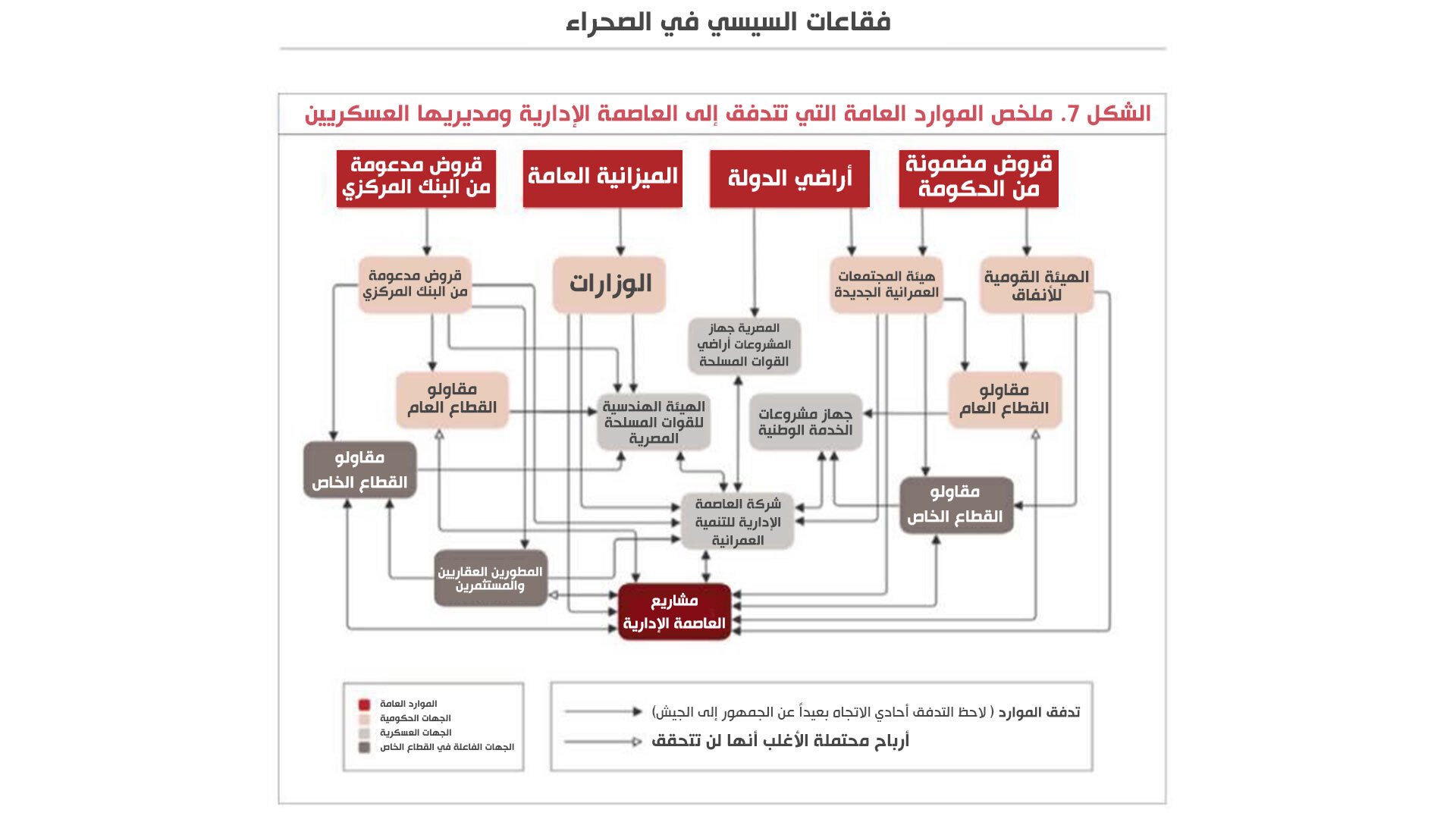

However, a recent report by the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED) contradicts this narrative, revealing that significant state funds, loans, and public resources have been directed towards the project—either directly from the national budget or through state-backed loans.

What Does the Egyptian Government Claim?

According to official statements, the NAC is funded through four primary sources:

1. Land sales to investors and developers

2. Private sector investments (both local and international)

3. Government-guaranteed loans for the project’s developers

4. Revenue generated by the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD), the company overseeing the project

However, financial records and economic analyses suggest that the Egyptian state has played a far greater role in funding the project than officially admitted.

How Was the New Administrative Capital Actually Funded?

The POMED report identifies four main funding sources for the project:

1. Direct Funding from the State Budget

• The Ministry of Housing, which owns 49% of ACUD, used its state-allocated funds to finance the initial construction phases, contradicting claims of an independent funding model.

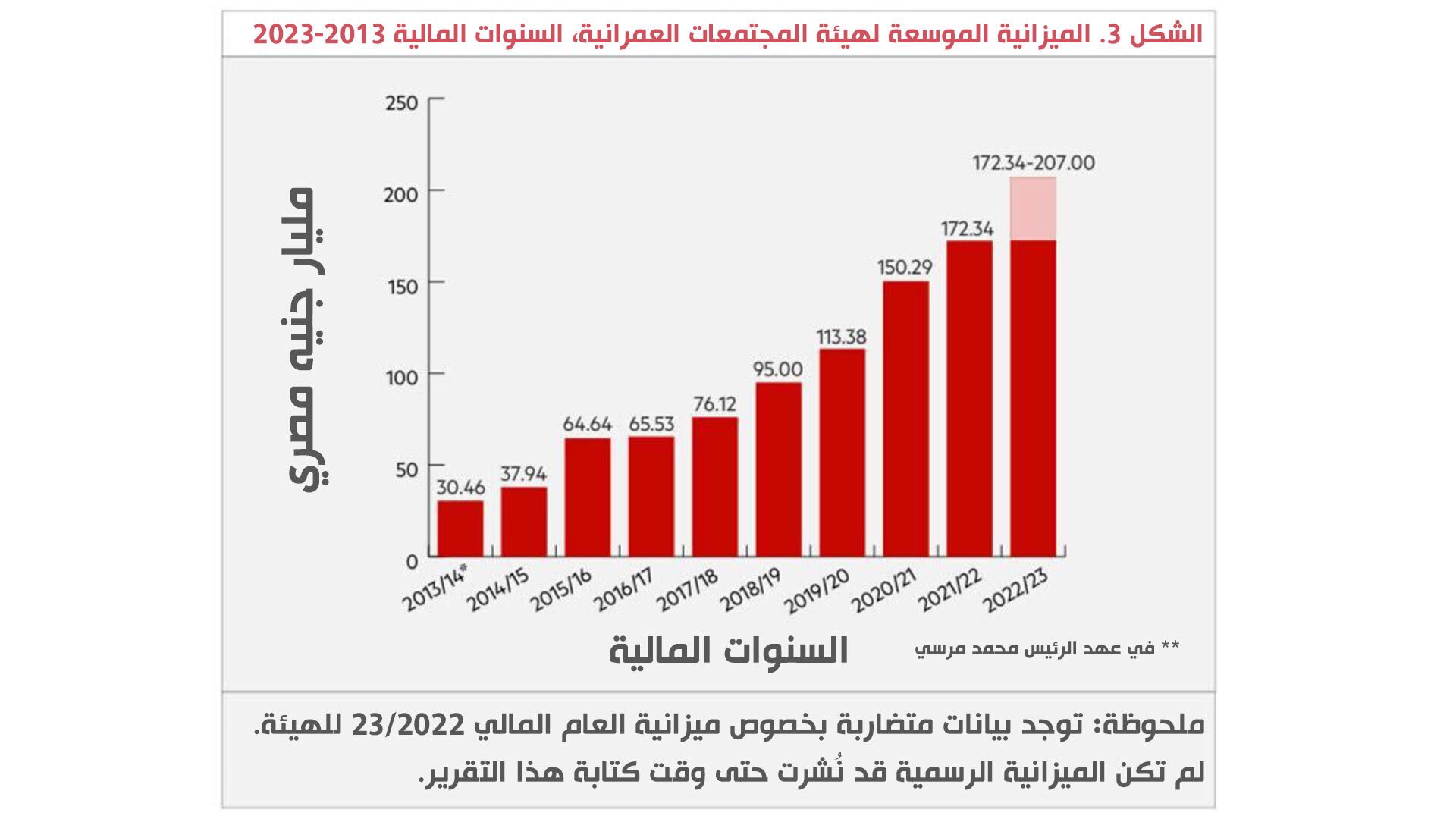

• The budget of the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA)—a government agency—surged from EGP 30.46 billion before the NAC to EGP 207 billion after the project began, signaling a massive injection of public funds.

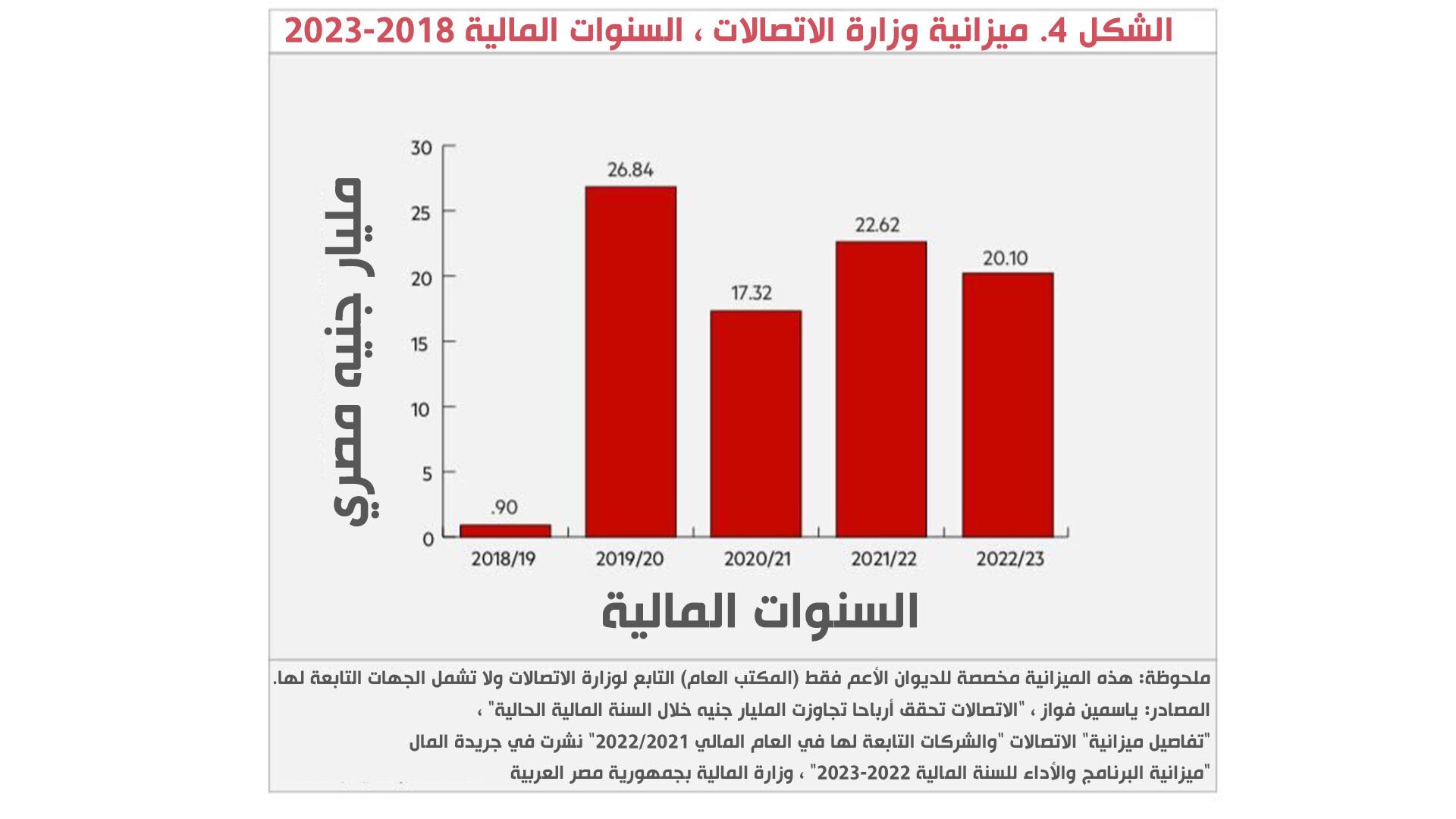

• The Ministry of Communications, responsible for the NAC’s technological infrastructure, saw its budget soar from under EGP 1 billion to EGP 26.84 billion following the project’s initiation.

• Water infrastructure for the NAC cost EGP 10 billion, including a 93-mile water pipeline connecting the capital to Cairo and 10th of Ramadan City. Another EGP 1 billion was allocated to pump water from the New Cairo area.

• The government classified water infrastructure for the NAC as a “public utility project”, justifying the use of state funds.

2. Public Land Allocations

• Large public land tracts were transferred to the Egyptian Armed Forces and NUCA.

• Essentially, state-owned land was reallocated to military entities, which then leveraged it for NAC development and sale.

• This land transfer mechanism benefits the military as the primary stakeholder, ensuring that proceeds from land sales are directed towards military-controlled enterprises rather than the public treasury.

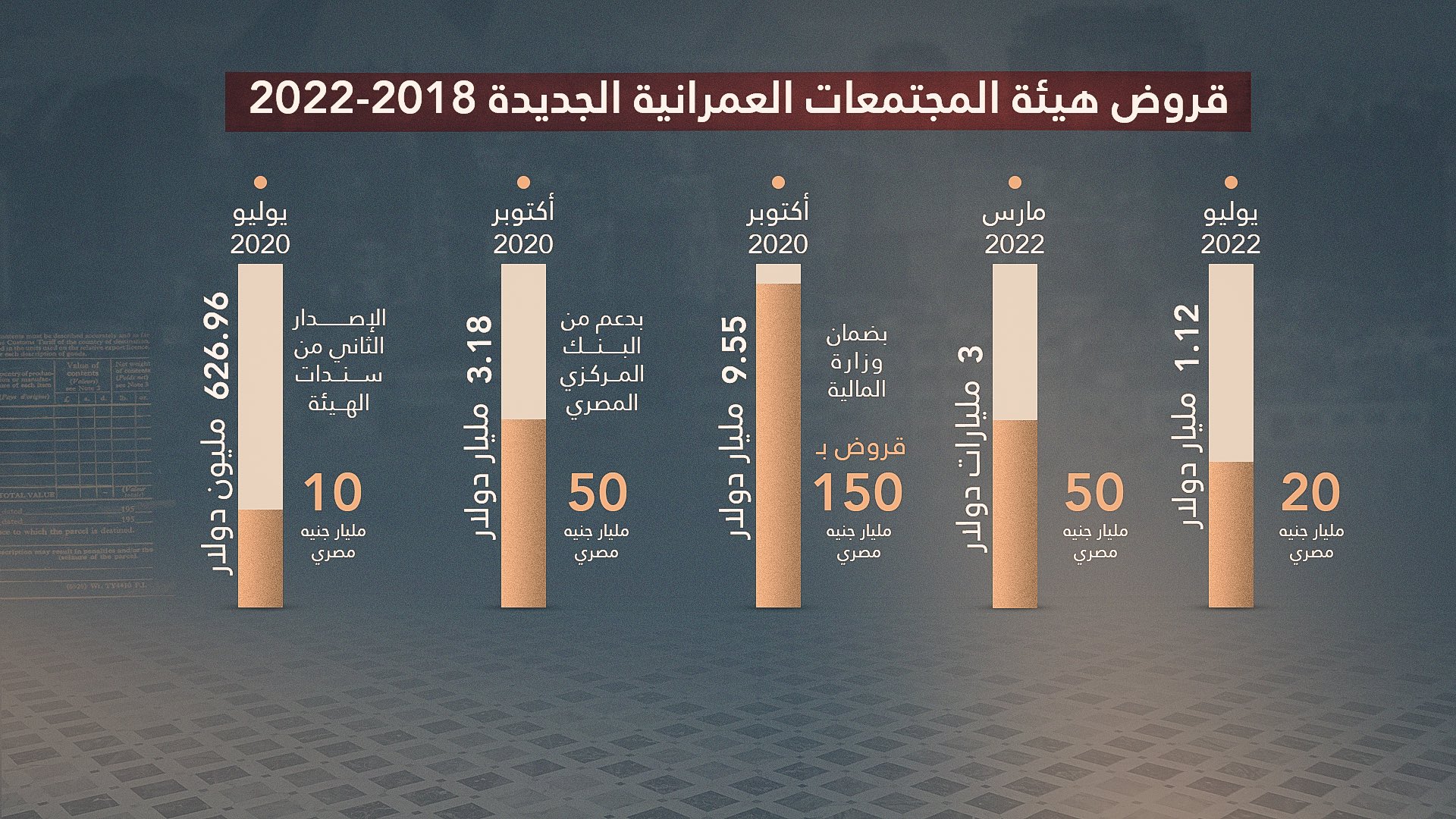

3. Government-Guaranteed Loans

• The NAC has been partially financed through massive foreign loans, totaling $52 billion in debt linked to the project.

• The Egyptian Ministry of Finance has guaranteed these loans, meaning that if the NAC fails to generate sufficient revenue, the burden will fall on Egypt’s public finances.

• Key infrastructure projects within the NAC, such as the monorail and electric train systems, were funded through government-backed loans.

Who Benefits the Most?

The financial structure of the NAC highlights how public funds and resources have been funneled into the project, benefiting a select group of military and government-affiliated entities:

• The Egyptian military controls 51% of ACUD, with key players including:

• The National Service Projects Organization

• The Armed Forces Land Projects Agency

• The Military Engineering Authority, which oversees construction contracts and infrastructure

This means that the majority of profits from land sales, investments, and commercial projects within the NAC flow directly to military-controlled enterprises, rather than into Egypt’s national budget.

Impact on Egyptian Citizens

The heavy financial commitment to the NAC has had serious consequences for Egyptian citizens:

• Social spending cuts: Government spending on subsidies and social welfare has dropped from 25% before the NAC project to just 11.6% in 2023, with further reductions expected.

• Currency devaluation & inflation: The mounting foreign debt burden has led to severe currency crises, skyrocketing inflation, and higher living costs, disproportionately affecting ordinary Egyptians.

• Exclusivity of the NAC: Property prices in the NAC are far beyond the reach of average Egyptians, positioning it as a luxury project catering to the wealthy and foreign investors, rather than a publicly beneficial development.

Conclusion: Is the NAC a National Development Project or a Military Enterprise?

The POMED report debunks the Egyptian government’s claim that the NAC is a self-financing project. Instead, substantial public funds, state-owned land, and foreign debt have been used to support its construction.

While the government promotes the NAC as a symbol of modern development, its financial reality suggests a centralization of economic power in military-controlled institutions—at the expense of broader national development priorities such as healthcare, education, and poverty reduction.

Ultimately, the NAC is less about national progress and more about consolidating military control over Egypt’s economy, leaving ordinary citizens to bear the financial burden.